These days, James Cameron is perhaps most known as a pioneer within the art of digital filmmaking. Beyond a new release, his films serve as technological demonstrations for the foreseeable future of the medium. None of which is to say his latest movies are bad; they just carry an additional facet that a lot of releases are unburdened with. Yet this wasn’t always the case. There was a brief period, early on in his directing career, when the expectation of breaking new technology ground wasn’t primarily on his audiences’ radars.

1984’s The Terminator is perhaps the purest of examples of this. A film that came out before anyone even knew who the then 30-year-old Canadian-born filmmaker was. Prior to the film’s development, Cameron worked at Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, making a living as a model maker and visual effects designer. It was here where Cameron landed a job as the special effects director for Piranha II: The Spawning. Cameron would ultimately go on to temporarily direct parts of the film’s sequel after its initial director would be fired for creative differences. Cameron would also be fired from the project (despite having his name kept on the closing credits), but he would not come away from the experience without the germ of an idea that would kickstart his career as a bona fide filmmaker.

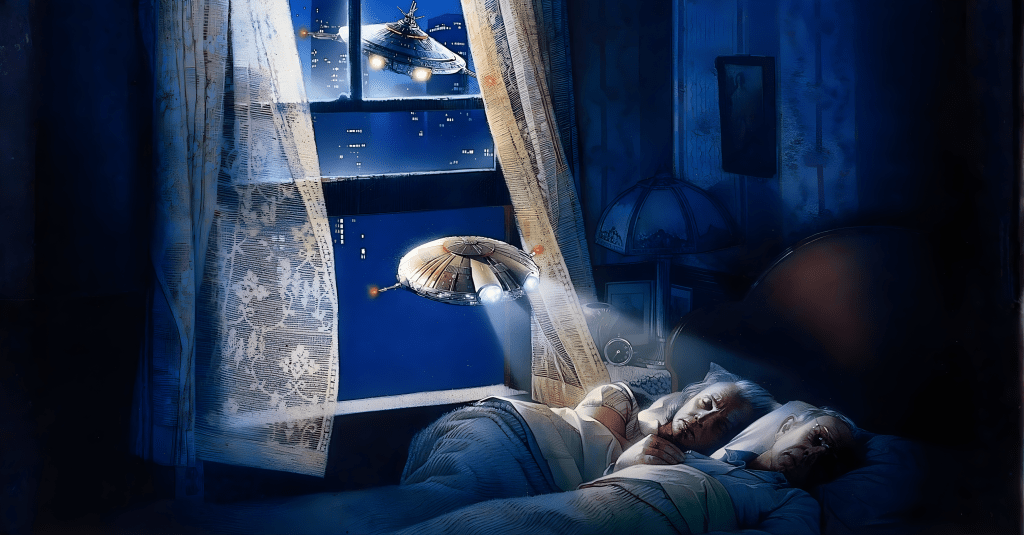

In the midst of the film’s production in Rome, Cameron would get sick and fall into a fever dream that blurred the lines between reality and imagination. In this altered state, he experienced a haunting hallucination of a chrome beast crawling from a wall of fire, its metallic skin reflecting the flickering flames surrounding it. With eerie determination, this creature used nothing but a kitchen knife to drag itself forward, carving a path of destruction and a sense of impending doom. This unsettling vision struck a deep chord within Cameron. The surreal nature of the dream ignited his creativity, leading him to produce a screenplay that would inevitably become The Terminator.

After his time on the set of Piranha II: The Spawning came to a miserable end, Cameron would busy himself with turning The Terminator into his first official directorial debut. Not that such a task was easy. At this stage in his career, Cameron lacked the financing and resources that would allow him to bring to life his visions in a manner that would fully satisfy him. So much so, he would essentially low-level remake the project seven years later. His vision for the story had a wide scope, depicting a future war in which killer robots and time travel made up part of the technological landscape. Despite the main bulk of the story taking place in the present day, the inclusion of endoskeletal beasts and flash-forwards to a looming future war made for a technically demanding screenplay. To bring such a project to life, Cameron would have to be smart and economical in his approach. He’d even have to gut significant parts of his script, reshaping it into a story that was more pragmatic from a production standpoint. Concepts such as his inclusion of a liquid Terminator would have to be shelved for a future sequel that had more technology and cash associated with it.

Then there was the fact that Cameron had yet to prove his worth as a director. Not an easy task when you haven’t had a proper opportunity to flex your filmmaking muscles good and proper. His time on Piranha II was short and doomed; certainly not enough of a gig to establish his strengths and weaknesses to future buyers of his work. It wasn’t enough for studios to take a chance on him. Pitching his script was no easy task, and any studio bigwig who did express interest in the screenplay did so with the desire for Cameron not to be involved in the production process. There was one who took a chance, however. Gale Ann Hurd had also once worked for Roger Corman as his P.A., and knew Cameron from his time working with the studio. Hurd saw potential in Cameron’s script and would buy it off him for $1 dollar under the promise that she’d keep him on as a director when (or if) the project finally got off the ground.

The Terminator was finally made and released in October of 1984. Funded by Orion Pictures, Cameron finally got his shot at directing the feature, and while it was made within considerable limitations compared to his future blockbusters (the final budget for this came to $6.4 million), we ended up with a finished product that was somewhat remarkable under the circumstances. Though far from perfect, this is a film that elevated itself above its competition, becoming a film that would establish itself as a classic for both the genre and the era it was made in.

At its core, The Terminator is a typical 80s B-movie that stands out due to its characters and central love story. While not the only B-movie with such traits, the commitment to these elements helps it rise above the many sci-fi and monster films of the time. It tells the story of a low-budget movie about a killer robot sent back in time to kill the mother of future resistance leader, John Connor. Themes of hope, love, and the complexities of humanity are central to the story, allowing it to blend multiple genres effectively and memorably. In essence, this becomes a B-movie that has a wide appeal for audiences, making the film more accessible and resonant to audiences with a wide range of tastes. A huge part of Cameron’s success is taking film genres – whether they are historical epics, love stories, sci-fi epics, and B-movies – and making them universally appealing. The Terminator, in many ways, his is first success of doing this.

The premise of The Terminator alone isn’t very remarkable. It’s not necessarily an idea that automatically has the potential to get bums on seats and have people talking about it for days. However, the film’s true power lies in its profound character development, which elevates the narrative to a more compelling status. Cameron skilfully crafts multi-dimensional characters, making them relatable and engaging for the audience. The film’s focus on character arcs enhances emotional investment, allowing viewers to connect deeply with the struggles and triumphs on sure at the heart of this story.

Sarah Connor is a fascinating example of this. These days, it can be easy to only view Connor through the lens of her powerhouse depiction of the character in the film’s 1991 sequel, Terminator 2: Judgment Day. Here, however, we get the evolution of that character in 107 minutes. As we are introduced to Sarah in this film, she is presented as your standard young woman living in 1980s America. She has a minimum-wage job, lives in a humble flat with her best mate, gets overwhelmed while at work, and tries not to cause a fuss when other members of the public are rude to her. Sarah’s purpose at this stage of the story is to serve as an audience identification figure. She isn’t the hero of a science fiction story but a surrogate who will allow audiences to see the strange tale that’s about to unfold through her eyes.

When the science fiction plot finally crashes into Sarah’s world, the character goes through an interesting transformation. There’s one scene in particular in which we see Sarah trying to make sense of the presence of a killer cyborg from the future. As Kyle Reese explains what’s happening to her, she’s skeptical, standoffish, and even attempts to escape Reese while he’s trying to get her to safety. What’s most interesting is how Sarah still listens to Reese despite her resisting his claims. By this point, Sarah has seen enough from Reese’s and the T-101’s showdown to recognize that something unnatural is at play here. She resists, but she is also not blind enough to flat out deny what she’s been told. Connor spends a great deal of this script battling with herself, fluctuating between relying on Reese and pushing back against his claims. She’s at war with herself, overwhelmed and frightened by the story she’s finding herself caught up in.

What makes Sarah such a compelling protagonist is her vulnerability and fear. Despite the film framing her as the mother of humanity’s future, it doesn’t turn her into an indestructible force of nature at the first opportunity. It shows us a very real and relatable person coming to terms with who she is and what she can offer to a world on the cusp of oblivion. Cameron has always been very good at creating characters who are both strong and vulnerable, never falling too far into either field. Sarah works so well here because she is an incredible force of nature who bleeds and cries just like the rest of us. She is a character who represents the best in humanity, yet she is just as flawed and fragile as the rest of us.

Kyle Reese is another compelling protagonist at the heart of this story. Like Hamilton, Michael Biehn delivers a solid performance that elevates the fragility of this character. Reese is a soldier from the future. He’s capable of hotwiring cars, stealing weapons from police officers and building bombs. From the moment he first appears on our screens, his capabilities are demonstrated without doubt. Yet Reese is also childlike in his behaviour. He doesn’t know how 80s society functions. He has absolutely no clue how to communicate with people; going so far as to expositing details to strangers that are guaranteed to get him sectioned by the authorities. Despite being her protector, there are moments throughout the film when Sarah will become almost motherlike to Reese. She will stop him from fleeing when the police surround them, will tend to his wounds, and will even help him pay for a hotel room with her own money. Much like Sarah, Reese will walk a balance between being a larger-than-live action hero, and a powerless child trapped in a world he doesn’t understand.

Cameron utilises Reese’s character to cleverly exposit plot information that cannot help but be clunky. Considering this is a film about time travel and robots, there is no easy way to deliver the story details to audiences without unloading heaps of clunky explanations. This film is not exempt from info-dumping. In fact, the second act has quite a lot of it. Cameron attempts to fold it into a chase and stealth sequence, yet it’s still in here for all to see. Yet there is a logic to Reese waffling on about future events. As we’ve already established, this is a man who doesn’t know how to interact with other people in 80s America. He was born in a wasteland, surrounded only by corpses and others in a state of survival. Having a character born into such circumstances find themselves transported into the midst of a civilisation is going to place Reese in a situation he is not equipped to deal with. It therefore makes sense to have Reese harp on about future wars, laser pulse rifles, and Judgment Day. He cannot comprehend a world in which people don’t take such comments seriously.

Arnold Schwarzenegger delivers a terrific performance as the Terminator in this movie: cold, calculated, and determined. What this film manages to do well is create a villain who wants the polar opposite of our heroes, all while making him a credible threat. There is something so simple yet petrifying about this villain: a calculated computer who doesn’t hold values pertaining to good or evil. It has been programmed to kill Sarah Connor and will do so by whichever means possible. While in future movies, the Terminators will exhibit behaviors that don’t make entire sense for a machine to engage in, the Terminator in this movie will only conduct actions in the name of its objectives. If it’s deemed impractical to murder or commit a crime at any point, it will not do so. If breaking the law will garner the fastest results, however, then it will sure as heck do so. The T-101 is an unstoppable force, incapable of being reasoned with. Schwarzenegger channels these motives to near perfection, delivering a convincing role of a robot wearing a skin suit.

Characters aside, this film furthermore stands out in terms of the love story at the center of this story. This decision wasn’t entirely Cameron’s idea, it would seem, as amplifying this facet of the script was a suggestion the director took from Orion Pictures’ show notes (they did also leave one about giving Reese a robot dog, but Cameron opted out of that one). Be that as it may, it was an idea Cameron made his own, applying a love story model he would revisit again later on down the line in his career.

Sarah and Kyle’s love holds startling similarities to that of Jack and Rose’s love story in Cameron’s 1997 smash, Titanic. Two people from wildly different backgrounds find one another in the shadow of tragedy. The two inspire one another before one is taken from them amidst the catastrophe. Changed by the short but intense love they felt, the survivor will go on, showcasing the values their departed love showed them were possible during their final hours. Kyle Reese is Jack Dawson, whilst Sarah Connor is Rose DeWitt Bukater. Kyle loves Sarah because she inspires him to see the best in humanity. Sarah loves Kyle because he sees a potential in her she never knew was possible. Kyle is taken from Sarah within hours of the pair substantiating their love.

Is it a perfect love story? Far from it. The way in which the revelation of Kyle’s love for Sarah is confirmed does come across as somewhat eye-raising. Cameron likes to use photos to symbolize what is going on in his stories. Again, we see this play out most prominently in Titanic, in which the camera pans past photos of Rose’s life as she lies in her bed dreaming/dying. It’s an effective mechanism to condense themes and ideas into momentary visual shots. In terms of what the photo represents, this does make sense within the context of The Terminator, yet on first watch, it can be a little jarring to hear Reese declare he fell in love over a photograph.

Having Kyle and Sarah fall in love in such a short space of time before one is taken is problematic in some ways too. For one thing, the idea of love stemming from another seeing worth in you almost seems to promote the idea that the root of love comes from being validated by an external source. After years of learning not to seek affirmation and approval from external sources (e.g., partners), I find it difficult to promote the idea of this being the foundation for a healthy love story. Then there is the notion that in order to become the best version of yourself, not only do you have to have another reveal your worth to you, but you must also lose them in order to grow.

Problematic associations aside, does this story work for me? The truth is, it does. Despite my issues with the central premise, Cameron’s doomed love story does tug at my heartstrings. It sure as heck did when he did it in Titanic, and it still works during his first attempt at it. Despite its problematic connotations, the idea of finding love that is transformative and life-changing is a fantasy that my brain appeals to on some level; the idea that some mystical angel will fall into my world and fill a void, even after that love passes. The fact that Sarah loses Kyle furthermore adds to the sadness central to this story. Much like Titanic, The Terminator is a story baked in tragedy. It’s a film in which our lead character must come to accept that in just over a decade, the world she has always known will be annihilated. Sarah and Kyle’s story is all about selflessness, essentially sacrificing themselves so that a future generation can go on to build a better future. This is a dark tale about loss and suffering. As unsettling as it may be to promote a love story built upon loss, in a film primarily constructed around the idea of losing everything, this kind of story helps to prop up the bittersweet note this story wraps up on.

The Terminator is a film directed by a prolific filmmaker at the start of his career. This is in no way the highly polished, impeccably crafted tour de forces we’ll see Cameron produce in the decades following its release. Some of the visuals are dated, the exposition is a little clunky, and some of the plot beats don’t come across as they may have been intended. Having said that, this film still stands tall in spite of its flaws. Cameron has managed to make a film that does hold up surprisingly well, 40 years after it was made. The models utilized for the war sequences look surprisingly convincing. Even the shots that elicit chuckles from modern audiences – such as the damaged Arnie/exoskeleton shot in the bathroom mirror – have impressive production designs that are hard not to admire.

While this might not be the envelope-pushing box office belters that will come to define Cameron’s career in later years, the signs of his greatness are undoubtedly on show here. He has managed to make a low-budget B-movie look more expensive and engaging than a lot of directors would have managed. He has taken a genre often accused of being cheap and lazy by its critics, and made a piece of work that elevates the genre to heights difficult to criticise. The characters are great, the story manages to exposit without grinding the entire narrative to a halt, and the love story elevates the tragedy to new heights.

It’s far from Cameron’s greatest, but it establishes a rock-solid foundation that will be used to build a remarkable career upon.

One response to “‘A Beast from the Third Degree’ – The Terminator”

Good post, I subscribed. Have a happy day☘️

LikeLike