It’s June of 1980, and director Steven Spielberg is prepping himself for his upcoming project. Despite his work with Ron Cobb, Rick Baker, and John Sayles, Night Skies is still far from ready to begin filming. The feature needs more time to gestate before entering production. But that’s fine, as Spielberg has another feature lined up at the ready; the George Lucas penned Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark. Considering we’re in a period long before CGI is able to whisk audiences off to digital deserts fashioned from the comfort of a Californian studio, Spielberg had to head off to globe-spanning locations to capture that blockbuster feel. To bring Raiders of the Lost Ark to life, shoots needed to take place in France, Tunisia, Hawaii and England.

Demands of travelling for work can be stressful at the best of times. This is especially the case if the work itself is chaotic and difficult. Turns out, Raiders of the Lost Ark would prove to be both of those things. The film’s script featured stunt-heavy set pieces; one of which sees Indiana and the movie’s Nazi menaces engaging in a high-octane race through the Tunisian desert. This would require Indiana to dash through sandy vistas on a horseback, whilst climbing onto trucks and into passenger seats. Once again, the lack of CGI meant all of this had to be done through stunt performances whilst operating heavy, fast-moving machine in sizzling temperatures. To make matters all the more taxing, the entire cast and crew also came down with a case of food poisoning after sampling some of the local cuisine. The experience was frantic, demanding, scorching hot, and punctuated with a grisly case of diarrhoea. Not exactly as appealing as sipping champagne with pending business partners in Venice.

Amidst the sickness, sizzling heat and strenuous work tasks; Spielberg’s mental state shifted somewhat. No longer did he appear to be in the experimental, brainstorming mindset he found himself in when asked to work on a Close Encounters follow-up. In his overworked, burned out, isolated state, he suddenly found himself less interested in breaking new ground in his extraterrestrial creative endeavors, instead wishing to return to something slightly more familiar. Night Skies, it would seem, wasn’t the type of story that would help him achieve such a goal. After all, his relationship with aliens stemmed back to a fascination he developed during more innocent times. It was a topic that filled him with excitement and wonder, not dread and fear. Going down the horror route at this point in his career when it came to cosmic visitors would have represented a huge shift from what he was familiar with. He felt the subject matter was too adult to meet the type of alien story his 1980s brain was yearning for.

But what would this mean for Night Skies? By this stage, people had come aboard to build models and draft out treatments. It wasn’t merely a notion floating about inside Spielberg’s head. It already had people attached to help bring this vision to life. The cogs were turning and workflows were in play. Retooling this idea into something completely different placed a question mark over the feature’s preliminary crew. The current team assembled were hired on the basis that Night Skies was to be a horror movie set on an isolated farmland. Transitioning from a horror story to an innocent fable would mean dismantling the entire project and rebuilding it from the ground up.

This change would inevitably extended to the writing staff. John Sayles had come on board specifically because of his involvement with the first Piranha movie. This reinvented project would therefore require someone new to help transform his Night Skies inspiration into something more family friendly.

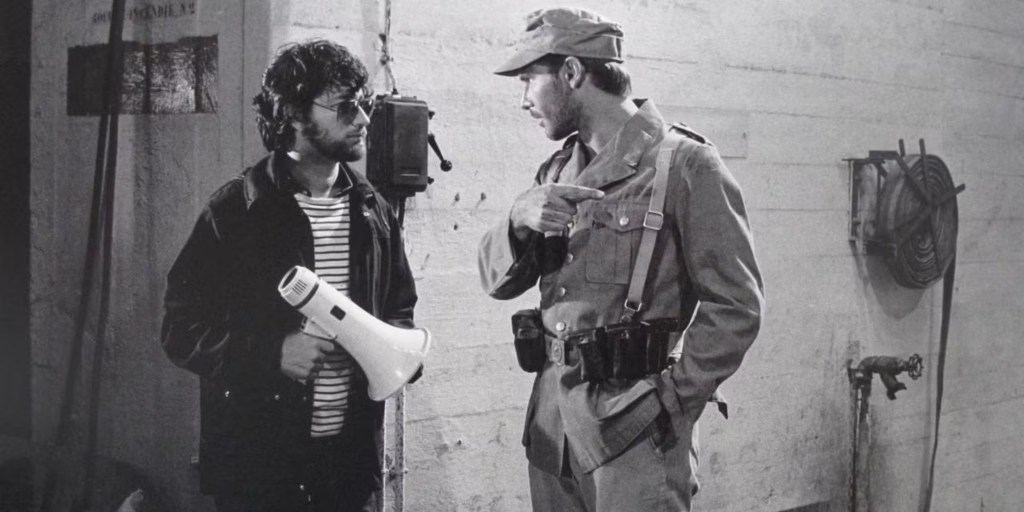

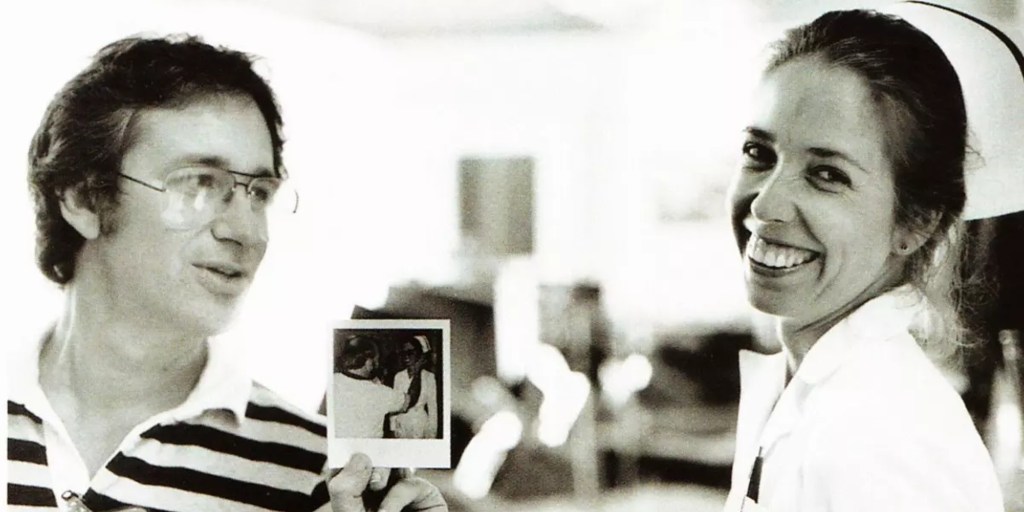

It was during his time working on Raiders of the Lost Ark that Spielberg first met the up and coming screenwriter, Melissa Mathison . She wasn’t there as a member of the creative team, but to visit the film’s star; Harrison Ford. The pair first met on the set of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now four years prior in 1976. The two became close over the years, and would eventually go on to establish a romantic relationship two years later in 1982. Their budding relationship meant that the then-30-year-old Mathison would become a regular amongst the cast and crew.

Mathison was born on June 3rd 1950. She grew up in a family of writers. Her mother, Margaret, served as the food editor for Fortnight Magazine. Her father, Richard, meanwhile, was the Los Angeles bureau chief for Newsweek. During her younger years, Mathison would baby sit. Amongst her clients were Sofia and Roman Coppola. Their father, Francis Ford Coppola, would become a vital connection in Hollywood for Mathison as she got older. The more he got to know her, the more Coppola would come to recognise what he called her ‘inquiring mind and interesting opinions.’ These characteristics were what inspired him into hiring her after she’d graduated from Berkeley to work as a camera operator on his 1974 film, The Godfather, as well as 1979’s Apocalypse Now.

Coppola noted how Mathison exhibited a love for writers and writing. She loved to read and had a thirst for learning new things. It was this keenness that inspired Coppola to encourage her to try her hand at writing; even asking for her help with the screenplay for The Godfather: Part II. Soon enough, Coppola encouraged Mathison to complete her first screenplay, The Black Stallion; a film about a young boy and his friendship with a horse.

Spielberg had been a fan Mathison’s The Black Stallion script prior to him even knowing who she was. The feature resonated with him due to its themes surrounding bonding, coming of age and self-discovery. Without realising it at the time, these would become ideas that would be weaved into his upcoming alien feature. His desire to explore extraterrestrial fascination wasn’t the only characteristic of his childhood he’d ultimately touch upon, as aspects surrounding his parent’s divorce would also make their way into the finished product. Around the period in which he was working on Raiders of the Lost Ark, he’d also been working on an autobiographical tale which would look at how the real-life divorce of his own parents had impacted his sisters’ and his sense of duty to take care of one another. Spielberg saw divorce as a catalyst which creates a responsibility void. This inspired him to want to write about a group of young siblings who felt such a void split wide open following the departure of their father. The three siblings at the heart of this tale would be fighting to find themselves in a home that had been shattered; all of whom would be trying to find meaning and a sense of responsibility in a home that now makes less sense to them. Little did he realise at the time, his autobiographical fancies would inevitably bleed over into his reassembled Night Skies project.

At the time of their first meeting, he was not aware that Mathison had written The Black Stallion, although upon spending more time with her, it is possible that this discovery may well have motivated him to start considering her involvement in the project. After all, this idea of a boy connecting with another species did already lie deep within the original Night Skies concept. The evolution of the friendship between Budde and the family’s youngest son was essentially a partially inspired retelling of the ideas found in The Black Stallion; whether intentional order otherwise. If this idea was brought to the forefront of this story, it could present a unique opportunity for a man desiring to return to his childhood routes. It would mean he could tell a story about a young person trying to fill the responsibility void left by a departing father, all within the scope of an extraterrestrial fable. This would widen the potential, allowing for a film to touch upon multiple themes that dominated Spielberg’s younger years; creating an opportunity Close Encounters never managed.

Although Close Encounters tapped into the wonder Spielberg experienced toward UFOs as a child, the film did not directly address his experiences surrounding his own family’s separation. There are echoes of these ideas in there, but not on a level that properly addresses them. For instance, Roy Neary’s abandonment of his family does touch upon this, all without acknowledge the consequences or harm it likely inflicted upon his wife and children. Crucially, we never see the fallout or consequences of this event from the children’s perspective. It’s only Roy Neary’s point-of-view we see, who is more wrapped up in the awe of sailing off to the stars. Spielberg even went on record during a 2005 interview with Cinema Confidential to acknowledge this decision, stating that he wrote it before having children”. It’s inclusion in the final script suggests in 1977, he was not yet ready to fully explore how his father’s separation from his mother affected him.

Spielberg began reading the Night Skies’ script to Mathison on the set of Raiders of the Lost Ark. The pair both agreed that amidst the film’s grisly tones, there sat an affectionate tale about a youngster befriending a creature from the stars. Mathison noted her admiration for this subplot, going so far as to be moved to tears by it. Spielberg also took note of the subplot’s potential. The thought of expanding it was so appealing to him that he decided to return to the director’s chair to helm this story; something which he had no desire to do when Night Skies was intended as a horror.

Considering The Black Stallion and its thematic and narrative similarities; it was felt that Mathison was the perfect fit to help bring the blueprint to life. Her handling of themes surrounding childhood bonds in her 1979 debut meant she had the sensitivity and understanding to tell this tale. Yet despite her interest in the project, Mathison was hesitant. She did not feel she had it in her to tell such a story. Spielberg was adamant, however. So much so, he started asking Harrison Ford to try and persuade her to reconsider. Eventually, Harrison arrived on set, booted from head to toe in his Indiana gear, declaring to Spielberg that he thinks he has finally persuaded her.

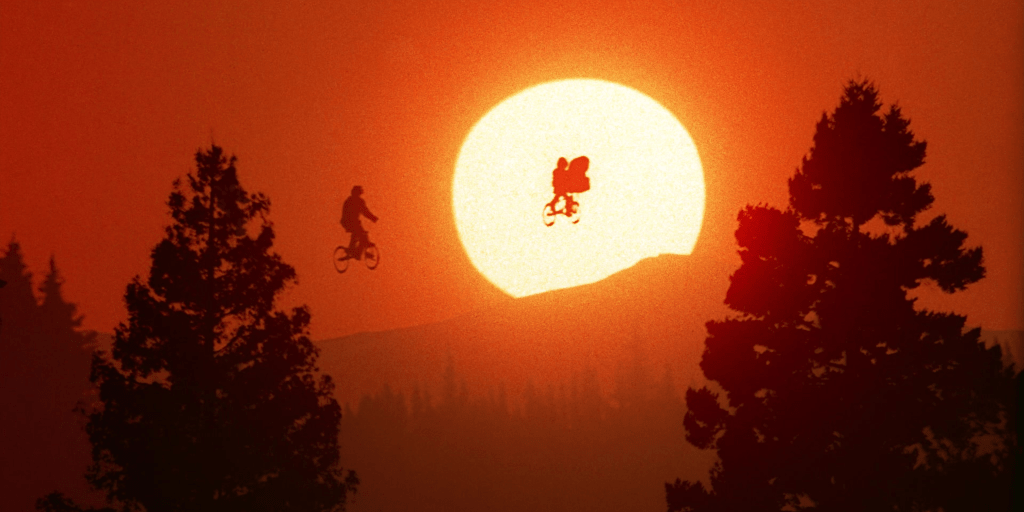

The persistence paid off. Mathison took away her notes on Budde and his human friend, then returned two months later with an entirely retooled screenplay. Gone were the mutilated cows, remote farmlands and psychic aliens. The Budde subplot was now central to the script. The void of responsibility triggered by an abandoned parent became the ultimate driving force behind the story; one which would be fulfilled resolved by the unexpected arrival of an alien child.

Mathison’s original title for the script was A Boy’s Life. This was not intended as a final name, but was called as such to keep its details a secret from rival studios. Spielberg’s rising fame, not to mention his existing success with Close Encounters meant he was a name many Hollywood execs had their eye on. Omitting any reference to UFOs or extraterrestrials from the title meant prying eyes would be much less likely to take a peek; should the opportunity arose.

At the time of writing, Mathison’s relationship with Harrison Ford began to deepen, and she became more central to his life. With this, came the deepening relationship between her and Ford’s two sons, Ben and Willard. With the inclusion of two young boys in her life, Mathison decided to take this as an opportunity to capture an authentic, child-like perspective. She asked the boys what they’d most like to see from a friendly alien, should one ever happen to find themselves visiting earth. The boys suggested telekinetic powers, similar to Yoda’s Jedi abilities in The Empire Strikes Back. One suggestion that stood out most to her, however, was the ability to heal immediate pain. What captured her attention most about this idea was the subtle difference in understanding that was meant by “pain”. The boy wasn’t on about healing life-threatening wounds or deceased animals. He meant taking away small, immediate pains, such as bruises, stubbed toes or cut fingers. It was the ability to cure immediate pains; something which to small children, are often considered serious due to their lack of understanding when it comes to wider, abstract reasoning. This aspect tied in perfectly with the story’s childlike perspective on the world. If Mathison was to capture the idea of childhood that Spielberg was chasing, it made perfect sense to focus on the healing as a cure to immediate, small scale injuries such as cuts, scrapes and bruises.

Her time babysitting during her younger years also helped Mathison as she drafted out A Boy’s Life. The numerous jokes, conversations and insults exchanged between kids meant that she was able to pick up the quirky and creative nature that can be found in younger people’s dialect. This allowed her to pen lines that sounded authentically childlike. Comments such as Elliot calling Michael “Penis-Breath”, Michael spontaneously likening E.T to that of muppet or frog, and Gertie asking Elliot if he “made” E.T are such examples of this.

Spielberg was amazed by Mathison’s first draft. So much so, he described it as so good, he’d be willing to shoot it the next day if he could. Records suggest that the quality of it meant very few revisions were made following the first redrafting. As happy as he was, however, minor revisions to Mathison’s story would take place throughout production; and Spielberg would inevitably remove a handful of scenes that would significantly reshape the overall feel of the final product.

One major revision included the ending of the film, which had an additional scene bolted on prior to the credits rolling. On the surface, this extended pre-credits sequence might seem trivial, however its inclusion would have almost certainly shifted the entire tone of the movie, potentially compromising the overall effectiveness of its final act. This version would have included a sequence following E.T’s departure. The scene would resemble the first time we see Elliot at the start of the movie, as he would be once again playing Dungeons and Dragons with Michael and his mates. As the game plays out, the camera would pan upward toward the roof of Elliot’s house. On the rooftop would lie the communicator E.T built to phone home. The communicator would be seen working away during this final shot, signaling that the boy and his otherworldly best mate were still in contact with one another. Keeping such a scene in after the final goodbye watered down the emotional gut-punch of E.T’s departure; weakening the heartbreak and sense of loss that Elliot experienced by getting E.T safely back home.

A less major example was a scene showing Elliot visiting his school’s uptight and condescending Principal following his “drunken” classroom antics. Perhaps most notable is that the Principal would have been played by Mathison’s boyfriend; Harrison Ford. This scene never made the final cut, as it was deemed to be too distracting from the story taking place. Furthermore, the fact that this film spends minimal time interacting with grownups is what helps to make the scene feel more childlike in its perspective. Having more scenes of Elliot conversing with adults beyond his own mother and the government agents searching for E.T would only serve to further dilute Speilberg’s child-centric approach to this movie.

Minor-cuts aside, Mathison managed to pen a screenplay that wowed Spielberg and retained most of its shape all the way up until post-production. Despite her initial doubts, she succeed in transitioning a story from a farmhouse horror, to a thematic exploration of Spielberg’s childhood; capturing the themes and relationship its creator had envisioned. All the more, she managed to put it all together in just eight weeks!

With a suitable script ready and waiting, all that was needed was to kickstart production; something which began on September 8th, 1981…

References

Bagley, S. (2015, November 11). Steven Spielberg on Melissa Mathison: ‘E.T.’s Glowing Heart’ Was Hers. Time. Retrieved from Time

Duquette, M (2015, November 5). Healing Hurts: Melissa Mathison and “E.T.”. Medium. Retrieved from Medium

Gainey, C (2022, July 27). The Multiple Versions of Close Encounters of the Third Kind Explained. Slash Film. Retrieved from Slash Film

Gilbey, R (2015, November 6). Melissa Mathison obituary. The Guardian. Retrieved from The Guardian

Lambie, R (2019, June 12). How Steven Spielberg’s Night Skies Became E.T. Den of Geek. Retrieved from Den of Geek.

Lewis, I (2022, April 23). Steven Spielberg says ET was inspired by his parents’ divorce. Independent. Retrieved from Independent

Leave a comment